LIVING THE DREAM

THE BEGINNING OF WORLD T.E.A.M. SPORTS

BY JAMES BENSON

WORLD T.E.A.M. SPORTS CHAIRMAN AND FOUNDER

I don’t think there’s a greater joy than to be on the receiving end of an unexpected positive situation or on the giving end.

Have you ever heard the term “butterfly effect”? The butterfly effect is a scientific theory that goes back about 100 years or so. It was developed in France, and the idea was that if a butterfly flaps its wings in Madagascar, it will influence the weather eventually in Nova Scotia. Meaning that all actions and activity has an impact will change the world forever. And, the term for that is sensitive dependence upon initial conditions. This has actually been proven supposedly in science over the course of the last 100 years.

I don’t know if it’s true in science, but I do believe it is true in human conditions. I think every action does have a ripple effect, and it does go out and change the world forever. If we had positive actions, positive things that we did would change the world forever. And perhaps, provide unexpected positive impacts.

I’m not a butterfly, I haven’t really done anything that would indicate the starting of something, but when I was in high school, I had two experiences. One, in particular, was transformative as far as experiencing the butterfly effect and the unexpected positive. I was a freshman in high school in 1960 in the little town of McHenry, Illinois. It was a little smaller at that time than Rice Lake, and a little bit larger than Wayzata. It was a very small town outside of Chicago, and we had a high school sports banquet. We had a speaker come to that particular banquet. His name was Ara Parseghian. At the time, Ara Parseghian was not the world famous coach of Notre Dame. He was the athletic director and football coach at Northwestern.

If you’ve ever heard Ara Parseghian talk, you know that he’s a person of passion, commitment and involvement. At our high school sports banquet, he talked about how important it was through sports to give back and be involved. I actually wrote some of his comments down, and I don’t think many 14-year-olds are writing things down at any sports banquet. So, I wrote down a few comments because it was very, very moving.

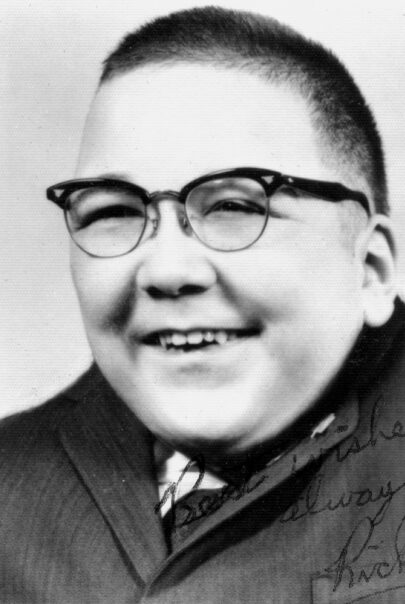

At about the same time, I met an individual by the name of Ricky Prine. Ricky Prine was an individual, a mainstreamed individual who was born with severe congenital birth defects. He was in a wheelchair. He could only move his hands and head a little bit. He was as disabled as you possibly could be physically, but he was as alive as you possibly could be – mentally and emotionally. Ricky Prine was a very bright young man. He went to the college prep classes as did I, and I was lucky enough to be his pusher. I heard that word used earlier today – I was the pusher of Ricky Prine for four years. While he couldn’t move his arms or legs, his mind was fertile and he never had a bad day. He had the best attitude of any individual I’ve ever encountered. I’ve never met a person who had a more joyous outlook on life than this severely disabled young man, Ricky Prine. He was our class valedictorian, went to the prom, and went to every game. He was as fully engaged in the life of this high school, McHenry Community High School, as a person could be. He was an inspiration to absolutely everyone.

A few years later, he died at age 24. I thought to myself there needs to be a way to help people like the Ricky Prines of the world get better opportunities. He died at age 24 – he probably should have died at age six according to his parents, but he did live a lot longer. I just sort of wrote that down. If I was ever an adult and in a position, I think maybe it would be a good thing to tell the story of the Ricky Prines of the world and give individuals like that an opportunity to have more of an opportunity in life.

Well, I got involved in the insurance business, and I forgot about Ricky Prine and about doing things. I did like everyone else. I decided I wanted to make some money, and I was a producer with the Management Compensation Group in Los Angeles, when MCGLA was a reasonably successful COLI organization. We are in the executive benefits business. They were heady days in 1983-1986, and making money was certainly a lot more interesting than being involved in community activities.

Ricky Prine as a senior in high school, 1964.

Photograph courtesy Lynn Henderson.

James Benson (left) and team members on the Kilimanjaro Confidence Climb, 1990. Photograph courtesy David Heffeman.

However, I met a person by the name of Steve Ackerman, who was one of our junior partners. Steve was involved with California Special Olympics. He invited me to a Special Olympics summer games at UCLA. Special Olympics as you might know, has to do with people with mental retardation – only mental retardation. There may be other disabilities, but everyone has a mental disability. I went to that, and I saw how these young people strive with their determination and bravery. In fact, the motto of Special Olympics is “let me win, but if I cannot win, let me be brave in the attempt.” I was actually blown away by the gentle guilelessness of these individuals and how they participated with one another.

Over the course of the next year or so, I was able to meet Rafer Johnson who was the decathlon champion and head of California Special Olympics, and got involved. But as things turn out, I noticed that maybe this is true, I don’t want to make any negative comments about southern California, but things tend to be a little glitzy out there, and it tends to be sort of celebrity driven. The California Special Olympics was no different than that. We would go to meetings and have fund raisers, but it seemed like there was an awful lot of attention based on celebrities, and who was there – not the athletes.

I was not interested in meeting Sheryl Crow or something (well actually, I would be interested in meeting Sheryl Crow if anyone knows her), but I was really more interested in working with the athletes. I found that when we did things together, it was a magical experience. The athlete felt validated and the person, the coach, the so-called able-bodied coach, felt better about what they were doing.

A year or so later, because I’d always wanted to ride a bicycle across the United States, I organized something called Ride Across America. We took 25 mentally retarded young adults, and in five stages, rode from Newport Beach to Mesa, Mesa to El Paso, El Paso to Austin, Austin to New Orleans, and then finally the last stage into Jacksonville Beach, Florida. It was a phenomenal experience. We were told we shouldn’t do this, because people with retardation should not be out on highways – it was dangerous. All of that was true, but in 26 days we rode 2,650 miles, 100 miles a day. Every day was an absolute winner. Every day was dynamite. The way these young people came alive.

We would take a 100 mile day, and separate it into ten mile segments. We’d have a support van that would go up five miles, and stop, so as we rode by the van, we knew we had another five miles to our rest stop. We’d get to the rest stop, we’d have sandwiches, Gatorade, Rocky would play, Chariots of Fire would play, we’d have a celebration and everybody that made that stage got a pin. Then we’d do another 10 miles.

Every day was like a joyous celebration going across the country. We were doing this not to raise money, but to raise awareness as to the capabilities of mentally retarded young people. There was a lot of press attention given to this, and we were put on Good Morning, America. On Good Morning, America there was a feed from New York into Jacksonville, and David Hartman was the host in those days. We had three people, myself and two of our athletes. One of the athletes was our most spirited rider, a young girl named Peggy Ann Kane. Peggy Ann Kane was being interviewed and David Hartman asked her among other things, “Well, Peggy Ann Kane,” because that’s how she wanted to be addressed, “how do you feel about this ride?” She said “Mr. David James Hartman I feel important.” Then he asked her why she felt important? And she said “Only important people, sir, get on television. Right now I’m on television, so therefore, sir, I must be important.”

That was a culmination of our trip. There was importance. Five people of the 25 on this particular trip were wards of the state of California. They had not gotten validation once in their life. Three people had never been in a restaurant before. We were taking a group of people and it was an incredible journey for them to be validated to be seen as part of society. As coaches, we saw the world in a whole different way. We saw that anyone can accomplish anything if you work together as a team.

James Benson (center) and team members relax during the Kilimanjaro Confidence Climb, 1990. Photo courtesy Cathy Griffin.

Unfortunately, David Hartman then turned to me and said, “Mr. Benson, you must be pleased with this success. What are you going to do next?” Of course, we had nothing planned next, we were just lucky that everybody survived this thing, but you can’t say that on national television. So, I shot out the two things that I wanted to do next. One was to run the Great Wall of China marathon, and the second was to climb Mount Kilimanjaro. I suggested that we were going to run in Beijing and also climb the most mystical mountain in the world, the most magical freestanding mountain in the world, the 19,342 foot Mount Kilimanjaro. He said that sounds very good. After saying that, then you have to try to follow through with it. So, we went back and we found that in China disabled people can’t run in the marathon. They can’t run at all, because with the one child policy in China and I don’t want to offend anyone, there aren’t any disabled people. At least there weren’t any disabled people of an age where they would be able to participate at that particular point in time. We scraped that idea.

But Mount Kilimanjaro was a good idea. We put together a team of 12 athletes. We did practice climbs in southern California. We put this team together. We went on a one month trip to Africa in January and February 1990, and it was a fabulous adventure. We had a television crew film it. David Breashears, now a world famous mountain cinematographer, was our cameraman. But we had some bad weather. We took our group of 12 athletes and 20 coaches to 16,000 feet and then it snowed for four days in a row. It snowed, and it snowed, and it snowed. Our guide said that we really couldn’t take the group all the way up. We could only take five athletes, five coaches and our experienced camera crew.

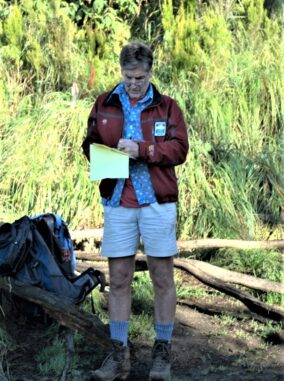

James Benson reviewing the itinerary for the day’s trek during the 2007 Return to Kilimanjaro Climb. Photograph by Arthur Chivvis.

So, we had to break the group into two and the one athlete, Patrick Halspice from San Rafael, California, a severely retarded person, but a gentle soul said it was okay. He and the other six would go down because if they didn’t go down, the others couldn’t go up and we’re all a team. So, this is just as an important part of being on the team. It was an amazingly adult thing for someone to say. If you’ve ever seen the film of that specific remark – it was captured on film.

Our five athletes and coaches made it to the top and went down and we were at the bottom of the mountain in Arusha. The seven who hadn’t made it up and the five who did got together. They blended together as a team easily and completely. There was no you made it and I didn’t. It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. The adults coaches who didn’t go up weren’t quite so happy, because they’d given up their chance. But the Special Olympians didn’t think there was any issue in that at all.

We also had a fellow by the name of David Hepernin go on the trip. David Hepernin was a beautiful athlete, 35-years-old and our oldest athlete, but he was an elective mute. He’s a very friendly person, a very happy person, but he didn’t talk. His parents didn’t know why he didn’t talk. He knew the words, and he was not so retarded that he couldn’t. He just would not talk. He was interviewed for the film. He wouldn’t talk. We get to the top of Mount Kilimanjaro, and we’re on our way down and he starts saying things, like he’s proud of himself.

We get to the bottom of the mountain and he’s actually saying sentences – that he’s proud, and he’s happy to have been part of the team. David Hepernin, at age 35 is coming out of his shell, because of doing something and being part of a team that he had not been part of before. He was part of a combined team of both able-bodied and disabled athletes, and he was pleased about that.

This was in February 1991. By June, he was speaking in complete sentences and telling his story to small groups. By November, he was an outreach spokesperson for California Special Olympics and he has been for the last 17 years. Just absolutely amazing.

But the most amazing part of that story didn’t happen on the mountain, it happened after the mountain. The television program was shown, it was well done, not that I had anything to do with it. CBS did a great job, and David Breashears did a great job. It won an Emmy award as the top sports film of 1990. As a result, the Million Dollar Round Table invited me and our athletes and some of our coaches to New Orleans in 1991 for the Million Dollar Round Table meeting. And at that meeting, after giving a little example of what was done on the mountain, the curtain pulled back and our 12 athletes appeared before the 7,000 to 8,000 people at the New Orleans convention hall and received a seven minute standing ovation. I know that Round Table crowds are very happy, very enthusiastic and welcoming of participants and individuals on the program. But seven minutes. It’s taped… it just went on and on and on. The validation given to these athletes and two of these 12 was the most amazing thing that’s ever happened to me – other than the birth of two children and my marriage date. It was June 24, 1991, the finest day of my life. And it’s all to do with the Million Dollar Round Table, and the welcoming spirit offered to these athletes.

As a result of that, I thought we had something that we could do and the very next day founded what’s known as World T.E.A.M. Sports. The T.E.A.M. acronym stands for The Exceptional Athlete Matters. We are combining people like Ricky Prine, maybe with a little more mobility, who don’t have a chance and we’ve had a chance to do some wonderful things around the world.

James Benson, in green jacket, rides his bicycle during the 2016 Face of America to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Tony Granata.

World T.E.A.M. Sports Chairman James Benson, left, talks with Vice Chairman Lon Dolber at the 2015 Face of America ride in Arlington, Virginia. World T.E.A.M. Sports photograph by Olivier Douliery.

I had a couple of other stories about interesting people who were touched, who had unexpected positive impacts brought on them. I don’t think we have time to go through those right now. But the point of the message is that in our business, we are connectors, networkers, and we all have the opportunity to be in the butterfly effect business. We all can do these things. We do it naturally in our business; we should do it naturally outside of our business. The life insurance industry has been enormously satisfying to me as an individual over 40 years, but frankly nothing compares to the things that have occurred over the last 20 years by working with people with various disabilities.

I did write down what Ara Parseghian said, and kept if for the last 46 years. It’s very short. Here’s what he thought as far as being in sports and being involved. He said, “Do all that you can with whatever you’ve got for as long as you can. Be fully engaged in all aspects of your own life, and be a positive influence in the lives of others. In some way, every single day do something, anything that helps someone else. They’ll feel good, you’ll feel good and our world will be a little better place in which to live.”

Adapted from a talk presented at the October 20, 2007 Top of the Table Annual Meeting.